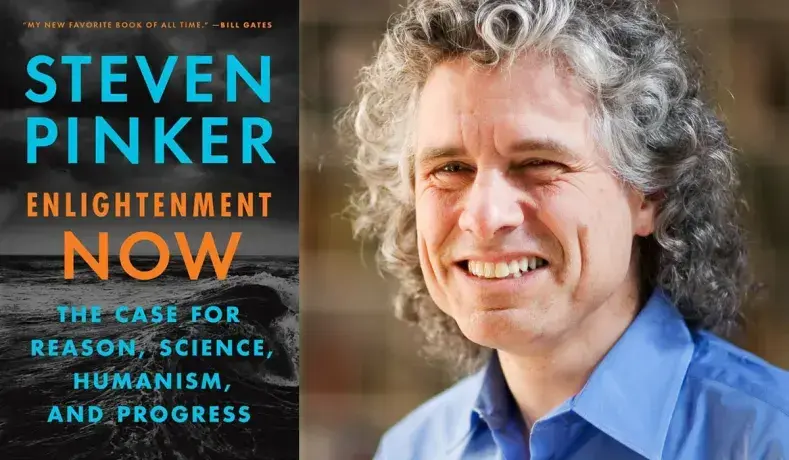

This is Part I of a series of blog posts on Steven Pinker and his book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. Read: Part II, Part III, Part IV

Steven Pinker, a McGill-educated Canadian who teaches at Harvard, is a so-called “public intellectual.” He is an influential high priest of humanism, an evangelist for the Enlightenment, and an anti-religious zealot. His views are often cited in discussions about science, faith, and reason, all of which provide context for understanding happiness, meaning, and purpose.

In this series of blog posts I will discuss Pinker’s views largely in relation to Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (New York, NY: Penguin, 2018), not because the book is good, but rather because he is a leading humanist and is representative of an uninformed, unsubstantiated, intellectually porous approach. So, it’s good to understand his perspective.

In short, the book falls prey to the grand narrative approach. An author cherry picks facts to fit a grand narrative. This makes for a great read, but as a work of fiction rather than fact. The sad result: a barrage of superficialities doesn’t produce a sound argument, like a hundred zeros still equal zero.

He vouches for reason but betrays his own principles throughout his book. This reminds me of the battles that Lord Nigel Biggar, Professor Emeritus, University of Oxford is fighting in the culture wars. While Pinker and his kin, the so-called progressive tribe, try to rewrite history to fit their narrative, Biggar, as a Christian, is the voice of reason and fact.

Pinker doesn’t define religion, faith, and Christianity properly, condemning and deriding millions and billions of people with snide remarks. As a humanist zealot, he says you don’t need God to do good, but his arguments are not compelling. Sounds good from the Ivory Tower, but that’s not the real world.

In most cases, in fact, God helps people do good.. A simple example and statistical fact is that people of faith throughout Canada are far more philanthropic than those of no declared faith. To take the example of evangelical Christians in Canada, the answer is a resounding yes. Apparently, the wallets of humanists are not opened due to the priests of reason.

The book's endorsements are like a roll call of humanists. Clearly, you need to be drinking the Kool-Aid to give this book credence. And, presumably, supporting Pinker that his view of humanism is the correct one.

Pinker seems to argue that virtually all good has come from Enlightenment ideals, such as reason, science, and progress, and that we just need to outgrow faith, religion, and the like. Despite all of Pinker’s arguments, people aren’t buying it (according to facts, which he claims to like). No doubt annoying to him, people keep adhering to religious and spiritual practices.

Despite a book with footnotes, references, and an index of about 100 pages, he omits glaring references.

In a 550 page diatribe, there is no mention of Jesus Christ or his teachings. Regardless of one's religious leanings, Jesus Christ would be consider one of the most influential figures in world history.

Pinker talks of “religious wars” without defining the term. His argument is that religion was the root of these wars. He fails to dig deeper and explore whether the leaders were after power and using religious gloss, or whether these were truly religious wars.

So, what is the Enlightenment? “The Enlightenment principle is that we can apply reason and sympathy to enhance human flourishing.“ [4] Further, it reflects “…the ideals of reason, science, humanism and progress” [4]

Throughout the book, Pinker juxtaposes these ideals against religion, his big bugaboo. Of course, it is a false dichotomy to pit faith versus reason and science (see John Lennox, Professor Emeritus, University of Oxford). Everyone has faith—it’s just a question of where it is placed. Pinker puts his faith in himself and his ilk; others put their faith in God.

In a battle between God and Pinker, I think God wins. For Pinker and his interpretation of the world, it is not enlightenment now, but closer to never.